In the 1970s, as the world marveled at the sleek lines and groundbreaking speed of the Concorde, Boeing had an even grander vision. The American aerospace giant set out to build a supersonic jet that would not only outpace the Concorde but would also be bigger and better in every conceivable way. The story of Boeing’s attempt to create the supersonic jet of the future is one of ambition, innovation, and ultimate disappointment.

The Dream of Supersonic Travel

The 1960s and 70s were an era of rapid technological advancements and high-flying dreams. The aviation industry was no exception. The Concorde, a joint venture between British and French aerospace companies, made its debut flight in 1969, capturing the world’s imagination. This slender, delta-winged marvel could cruise at Mach 2, twice the speed of sound, cutting transatlantic flight times in half. For the first time, commercial passengers could cross the Atlantic in just over three hours.

But while the Concorde was a technological marvel, it had its limitations. It was small, seating only around 100 passengers, and it was expensive to operate. Its sonic booms also restricted where it could fly, limiting it primarily to transoceanic routes. Boeing, however, saw an opportunity to go further.

In 1963, the U.S. government launched the Supersonic Transport (SST) program to build a commercial jet that could surpass the Concorde. Boeing won the contract to design and develop this new aircraft, which would be known as the Boeing 2707.

The Boeing 2707: A Bigger and Faster Vision

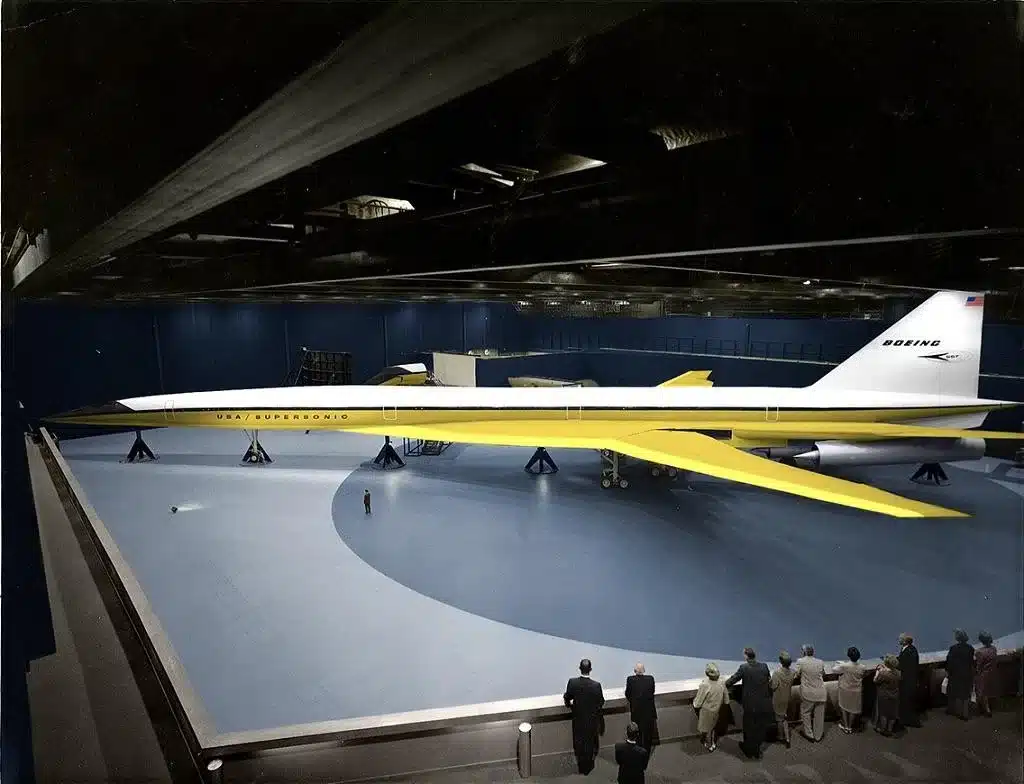

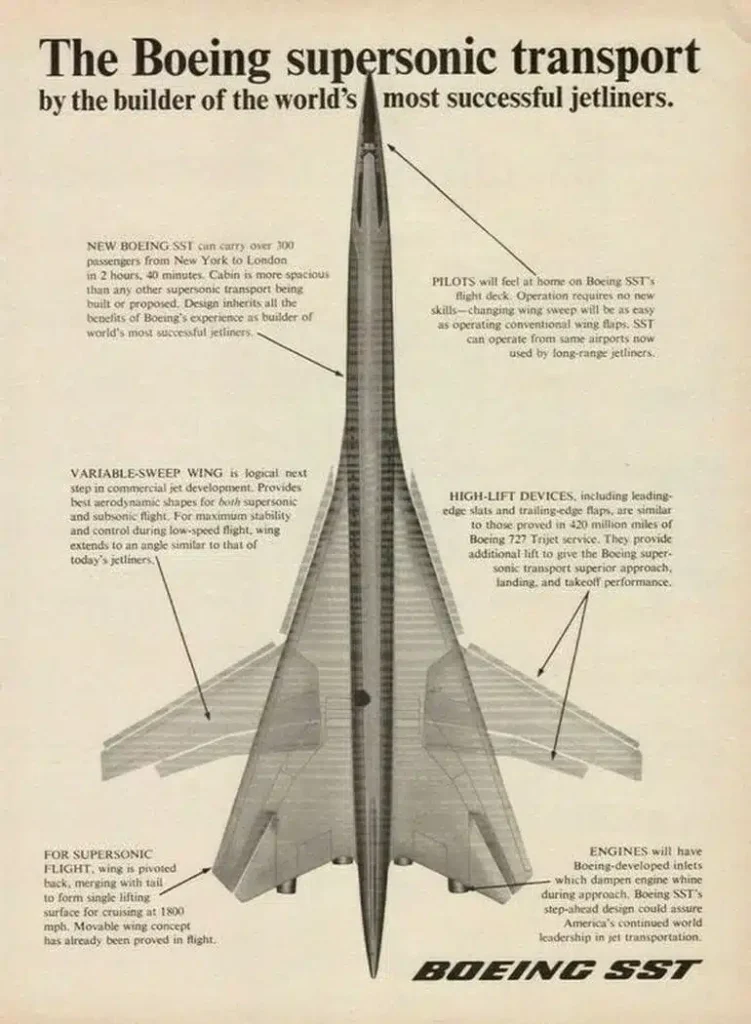

The Boeing 2707 was conceived as a supersonic airliner capable of carrying up to 300 passengers, nearly three times the capacity of the Concorde. The initial design featured a swing-wing configuration, allowing the wings to sweep back during supersonic flight and extend forward during takeoff and landing. This design was meant to combine the high-speed efficiency of a delta wing with the low-speed stability of a conventional wing.

Boeing’s engineers envisioned the 2707 cruising at speeds of Mach 2.7, significantly faster than the Concorde. The aircraft would be able to fly from New York to London in under three hours, making it the fastest commercial jet in the world. The larger size and higher speed promised to make supersonic travel accessible to more passengers and more routes.

However, the challenges of building such an ambitious aircraft quickly became apparent. The swing-wing design proved to be complex and heavy, requiring advanced materials and engineering solutions that pushed the boundaries of 1960s technology. The engines, capable of producing enough thrust to propel the aircraft to Mach 2.7, were also a significant technical challenge. These engines would need to operate efficiently at both subsonic and supersonic speeds, a requirement that was difficult to meet.

The Dream Unravels: Challenges and Setbacks

Despite these challenges, Boeing pressed on with the development of the 2707. The company invested millions of dollars in research and development, building prototypes and testing new materials. However, as the project progressed, it became clear that the technical hurdles were greater than anticipated.

The swing-wing design was eventually abandoned in favor of a fixed-wing configuration, which simplified the engineering but reduced the aircraft’s efficiency. The weight of the aircraft continued to be a problem, requiring even more powerful engines and more advanced materials. As costs skyrocketed, the project began to lose support.

Environmental concerns also began to take center stage. The 1970s were a time of increasing awareness of environmental issues, and the sonic booms produced by supersonic jets became a major point of contention. Communities across the United States and Europe expressed concerns about noise pollution and the potential impact on the environment. The cost of developing quieter, more efficient engines added yet another layer of complexity and expense to the project.

The oil crisis of 1973 was the final blow. As oil prices soared, the economic feasibility of operating a supersonic jet came into question. The 2707, already expensive to develop, would have been prohibitively costly to operate. Airlines, facing rising fuel costs and economic uncertainty, were reluctant to commit to such a risky investment.

The End of the Line: Boeing’s Supersonic Dream Fades

In 1971, after nearly a decade of development, the Boeing 2707 project was canceled. The U.S. Congress, facing mounting pressure from environmental groups and budgetary constraints, withdrew funding for the SST program. Boeing, unable to secure private investment, was forced to abandon its dream of building a supersonic jet.

The cancellation of the 2707 was a significant setback for Boeing, both financially and reputationally. The company had invested heavily in the project, and its failure left a lasting impact on Boeing’s approach to future projects. The 2707 remains one of the most ambitious aircraft that Boeing ever attempted to build, a symbol of the company’s willingness to push the boundaries of aviation.

While Boeing’s supersonic ambitions were never realized, the legacy of the 2707 lives on. The lessons learned from the project influenced the development of future aircraft, including the Boeing 747, which became the workhorse of international travel in the decades that followed. The 747’s success helped Boeing recover from the financial losses of the 2707 project and solidified its position as a leader in the global aviation industry.

Legacy and Lessons Learned

Today, as new companies and governments revisit the idea of supersonic travel, the story of Boeing’s 2707 serves as a cautionary tale. The dream of faster-than-sound travel remains alluring, but the technical, economic, and environmental challenges are as relevant today as they were in the 1970s.

Boeing’s attempt to outpace the Concorde was an ambitious project that pushed the limits of what was possible in aviation. While it ultimately failed, it also highlighted the risks and rewards of pushing the boundaries of technology. The story of the Boeing 2707 is a reminder that even the most visionary projects can be brought down by the harsh realities of engineering, economics, and environmental concerns.

In a world where the pace of technological advancement continues to accelerate, the lessons of the 2707 remain as relevant as ever. The challenges that Boeing faced in the 1960s and 70s are the same challenges that today’s engineers and entrepreneurs must overcome if they hope to make supersonic travel a reality once again.

As new supersonic jets begin to take shape in the 21st century, Boeing’s bold attempt to create a supersonic jet bigger and faster than the Concorde will be remembered as one of the great “what-ifs” of aviation history.